Bringing back the stories

you love—no paywall, just joy.

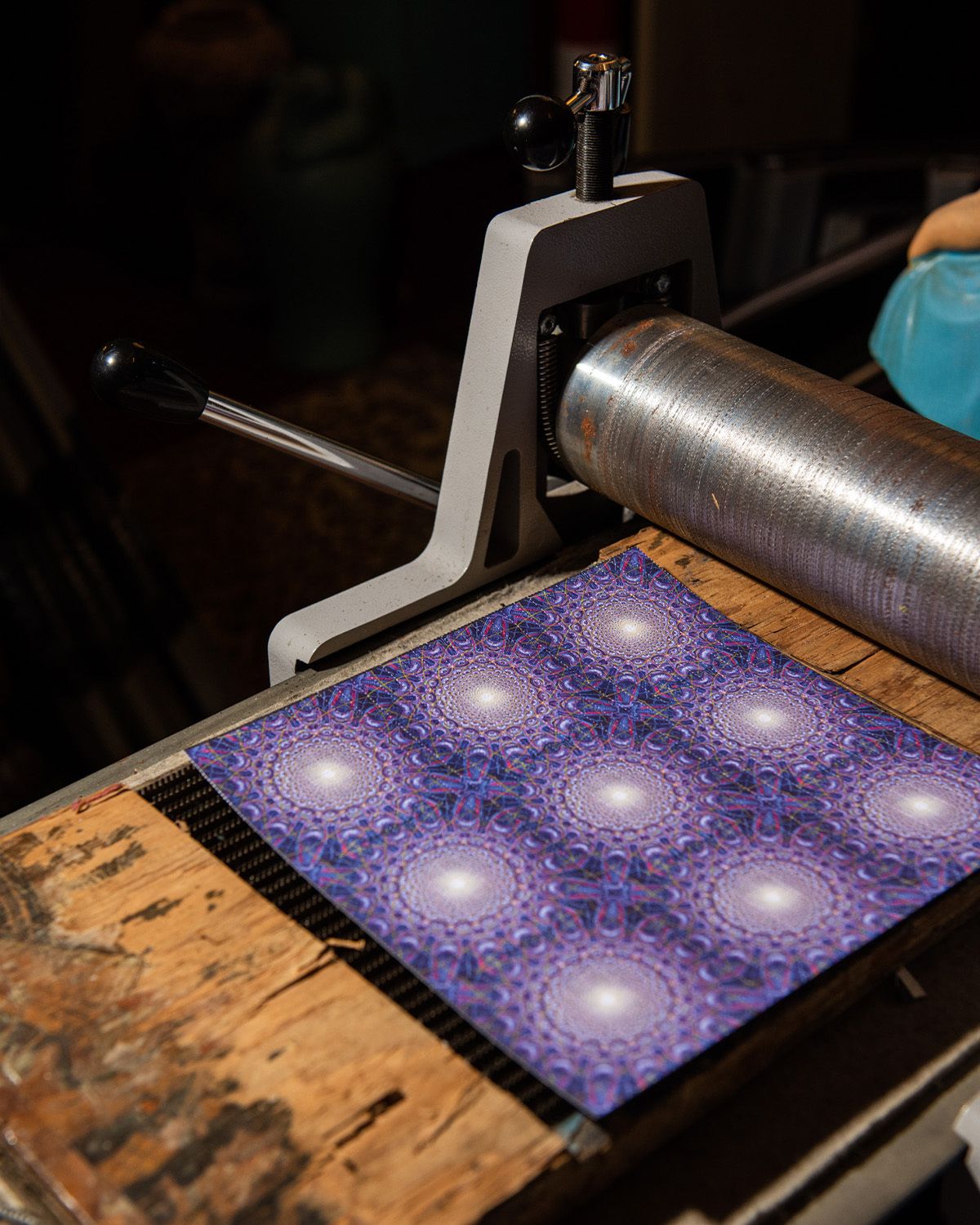

Inside the World's Largest Collection of Acid Tabs

Mark McCloud has been collecting LSD art for decades—but the reason behind his devotion to acid might surprise you.

By Madison Margolin

Photos by Jessica Chou

The underbelly of San Francisco—a city of whimsy, magic, and the downright weird—has been all but swallowed up amidst the shadows of Silicon Valley, with microdosing tech yuppies having come to outnumber the heads, who once painted the town a living art piece with historic (and heroic) doses of LSD. But still, the city abounds with vestiges of the past, offering windows into a future that glimmers with the promise of a second chance at authentic psychedelia. On the freak flag road to renewal is the headquarters of the Old School—a once favorite stalk-spot by the FBI (more on that later)—better known by those who know as Mark McCloud’s blotter art museum.

Stepping through the front door to McCloud’s Mission District Victorian mansion, time stands still; I wonder which psychonautic celebrities have walked through this very vestibule, into a sanctuary immemorial— untouched by the cycles of the seasons and decades past—because here, the sun literally don’t shine. The corner seat on the couch is worn in from visitors like me who’ve come to survey McCloud’s collection of 30,000 tabs of acid framed behind glass, hidden from the outside world by black velvet drapes—meant to block out natural light, but lending an eerie air to the decrepit place, tucked away from the straight world as a time capsule.

Continue reading after our partner message below.

Learn AI in 5 minutes a day

This is the easiest way for a busy person wanting to learn AI in as little time as possible:

Sign up for The Rundown AI newsletter

They send you 5-minute email updates on the latest AI news and how to use it

You learn how to become 2x more productive by leveraging AI

Bending and twisting our perception of time is psychedelic afterall, beckoning our souls to dance between the realms unfelt in mundane existence. McCloud has ample experience under the auspices of those otherworldly realms, having traversed the psychedelic terrain of death and rebirth.

“You get a mulligan if you die on acid,” he gabs through a playful grin. His gaze back at me flickers with suggestion; this wasn’t the clichéd type of “ego death” story common among seasoned psychonauts. Nay, this was actually morbid.

I glimpse around the room as McCloud keeps talking—he’s verbose, but for good reason, sitting upon multiple lifetimes of stories, expressed through the art and tchotchkes that clutter his living room. Imagery of skulls and the devil, portraits of Timothy Leary, Ram Dass, and Albert Hofmann, sayings like “LSD: Let’s Stop Destruction” or “LSD: See Your Travel Agent.” I notice a WiFi network titled “FBI surveillance van”—a new, mysterious phenomenon in the area, McCloud says, noting that time when the feds hunted him down, twice, and charged him for conspiracy to manufacture and distribute LSD.

But when you’ve died—like, actually had the life knocked out of you, albeit temporarily—not even the FBI or a bit of prison time can phase you. It’s just all part of the grand trip. Verily, McCloud was that guy tripping on acid, who fell from a window. “I was pre-med at Santa Clara, and I took a bunch of Orange Sunshine, and accidentally go out a seventh-story window at this place called the Swing Building,” he recounts, detailing the sound of his bones crushing as he plunged to his face. “I got into the magical enterprise of dying on LSD,” McCloud says. “And I know that the only reason I came back is that I was on acid—I could navigate the extremely infinite pathway of what was then called the Rainbow Bridge, the voyage between life and death, corporal and discorporal, dying and coming back to life. That’s the miracle of the mulligan.”

“I got into the magical enterprise of dying on LSD.”

In golf (which McCloud says the Scottish invented as “an excuse to hunt for mushrooms”), a mulligan is a second chance, a magical event that is “the mercy of a do-over.” Declared dead on the spot, whilst tripping through the whole ordeal, he narrates the journey of his soul leaving his body, making a first stop in Hell, before ascending to Heaven, where he was offered another shot at life in Mark’s body. “It was a metaphysical event, rather than a religious event,” says McCloud, who, having been raised Roman Catholic from Buenos Aires, had a religious enough upbringing to know the hallmarks of a bonafide miracle. “The metaphysics of it allowed me to have the special situation called a mulligan, where the interconnectedness of all things is so visible and accessible to you that you can arrange your second chance, or in this case access to the body that you left.”

And so McCloud made his home a shrine to LSD “to thank it for saving my life,” he says. “The smallest way I could pay my debt was by showing off the glory of the manufacturers’ vision expressed by the blotter itself.”

It took some time for the acid born-again to restabilize his mind after that fateful fall. McCloud dropped out of Santa Clara, declaring himself an artist—a move that got him disinherited by his family and thrown out on the street (“the best thing that ever happened to me”). And so he moved to Paris to study at L’Ecole du Louvre, and to avoid the Vietnam draft, before enrolling in an MFA program at the University of California, Davis once President Nixon left office. Upon graduation, he made the pilgrimage up to San Francisco, “the only place on earth that was showing my work.” To “milk this gallery situation,” McCloud immersed himself in the Bay Area scene as a collector and working artist.

A two-time grant recipient from the National Endowment for the Arts, McCloud’s first grant came from Jimmy Carter and the second from “Ronny Reagan—enough to put a downpayment on this house,” he chuckles. “I always say, the government bought me this house.” The irony being, the feds never quite took their attention off the house either, McCloud says, recalling when FBI agents rented flats in the neighborhood and would stalk him at the corner donut shop until the pounce. Each frame adorning the teal walls still has a small piece of tape stuck to it, numbered by the FBI— evidence!—in a former case that tried to label McCloud as a kingpin. “I’ve been acquitted twice,” says McCloud. “And I’ve always done it the same way: When I pick my jury, I’m on LSD.”

He’s got plenty of it—yes, some of those framed blotter sheets may even be dosed— but he doesn’t exactly claim ownership over his collection. “When you’re an acid head, you know it’s not really yours, but you’re doing it for the group,” he says. “So that my kid will understand. It’s done out of love.”

As for San Francisco’s new school, McCloud says the youngins—yes, the microdosers and the techies, too—are all his children. “It was known that you could come here and get turned on,” he reminisces, but adding, still, that “San Francisco is where you come to set yourself free.” The city by the bay is due for its own psychedelic mulligan, but this one is more internal, more metaphysical: Perhaps the hippies are fewer and more far between, but those like McCloud are still here, holding it down, and never stopped tripping. The city’s mulligan is in the renewed insights that psychedelics offer its residents—a chance to experience the other side, to get a second lease on how to see mundane life thereafter. And that perspective, McCloud says, is the greatest psychedelic treasure of all. “San Francisco itself, is the symbol of being as far west as you can go in the evolution of man,” he says. “And from here, you take off.”

How'd you like today's story?

💌 If you loved this email, forward it to a psychonaut in your life.

Editorial Process

DoubleBlind is a trusted resource for news, evidence-based education, and reporting on psychedelics. We work with leading medical professionals, scientific researchers, journalists, mycologists, indigenous stewards, and cultural pioneers. Read about our editorial policy and fact-checking process here.