Deep dives and investigations

you won't find anywhere else

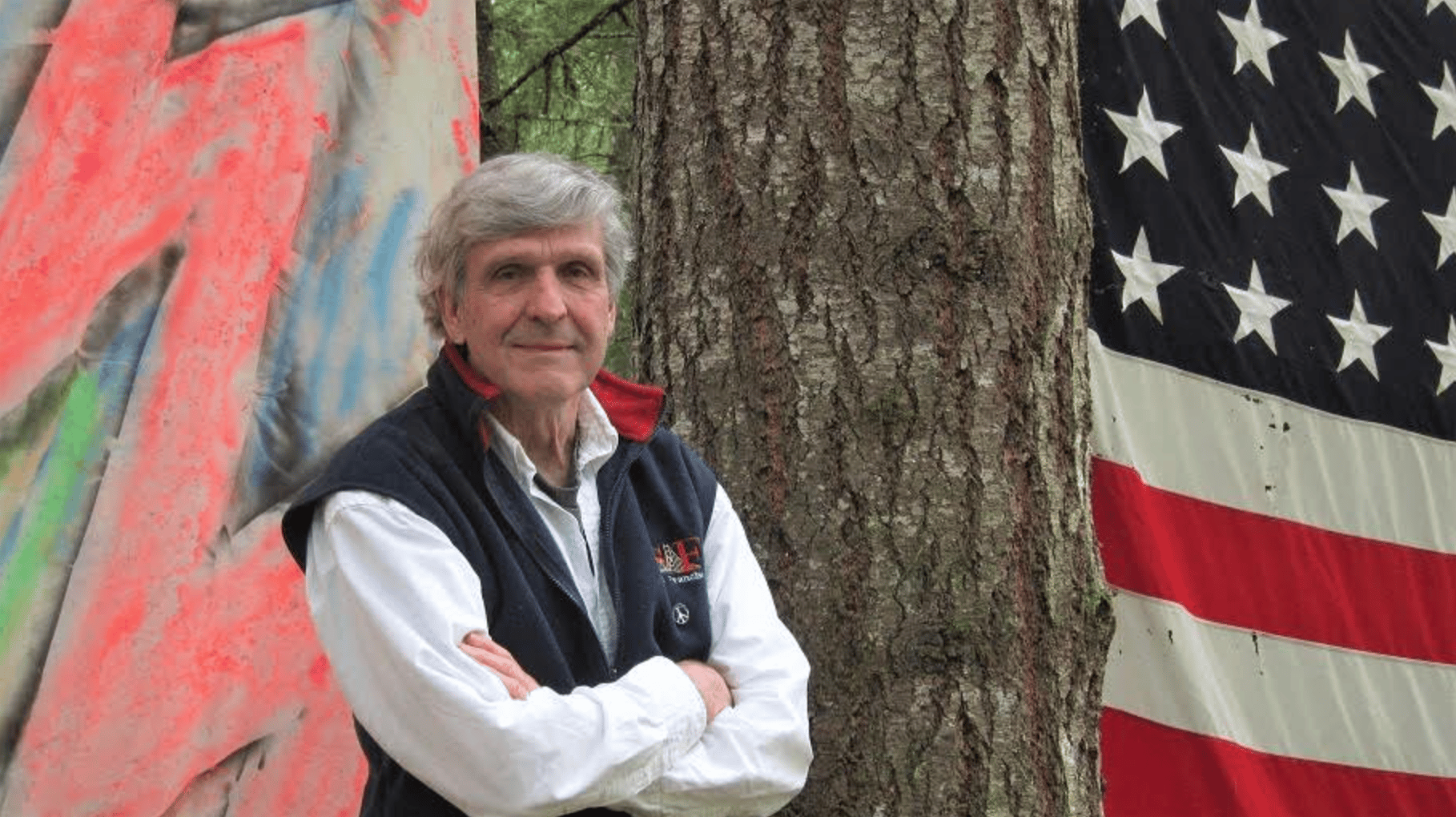

Ken Babbs, the Merry Pranksters, and the Birth of Psychedelic America

At 90-years-old, this writer and Merry Prankster reflects on the experiments, performances, and acts of storytelling that helped shape a distinctly American psychedelic culture, long before it had a name, a market, or a regulatory framework.

By Gregory Daurer

Call Ken Babbs the Washington Irving of West Coast psychedelia. In writing about his storied life within his recent book Cronies, a Burlesque: Adventures with Ken Kesey, Neal Cassady, the Merry Pranksters and the Grateful Dead (2022), Babbs utilizes the “burlesque” literary form that Irving pioneered in the early 19th Century—namely, ”an historical accounting with additions, exaggerations, embellishments and inventions.”

Throughout Cronies, Babbs uses creative license to recount a series of formative events:: Meeting Ken Kesey in a Stanford University writing program in 1958, prior to the publication of his celebrated novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest; Kesey's early experience with LSD as a paid volunteer at the Menlo Park Veterans Hospital at the dawn of the '60s; Babbs' own life after piloting helicopters in Vietnam (he wrote the novel Who Shot the Water Buffalo? based on what he witnessed in the early '60s); and the inspiration behind the Merry Pranksters' moniker. He also describes the Pranksters’ 1964 bus trip from California to New York, which included acid-fueled journeys along the way; meeting three real-life characters immortalized in the novel On the Road: the book's author Jack Kerouac, the poet Allen Ginsberg, and Neal Cassady, a juggler of an orator and the primary driver of the Pranksters' bus Further (aka “Furthur”); participation in the Pranksters' acid parties, including one hosted at Babbs’ house in Soquel, California, before the more public-facing Acid Tests; his long association with the Grateful Dead, including joining them onstage at Woodstock; and catching glimpses of Tom Wolfe as he researched his 1968 book The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test..

Babbs, who describes himself as “not mean, just ornery,” was born on January 14, 1936 — a birthday touched on at the beginning of the following interview, which took place by phone in early January 2026. He's still splitting wood at his home near Eugene, Oregon.

So, how does it feel to reach the milestone of 90-years-old?

BABBS: I feel with my hand, with my fingers — outreaching all the time, what's going on out there. And I stroke the flowers, pet the dog, and hug my wife. Everything seems to be doing okay.

The Merry Pranksters recorded a lot of their imaginings, their spur-of-the-moment stream-of-consciousness talk, or back-and-forth dialogues.

That's what we always did. We recorded everything. That was part of our whole scene: when we were doing something, we recorded it. We recorded either audio or video, or both. So, we ended up with all the tapes and film reels.

It had never occurred to me that the Pranksters were all dressed similarly with those striped shirts, because you were filming a movie, and you wanted some consistency in the look of the movie you were filming during your bus trip.

That's exactly right. That's why we did that.

In terms of making the movie and being the Merry Pranksters and going on the historical bus trip, you write, “Kesey was the chief who laid out the plans and assigned the roles to be played. [Neal] Cassady was the workingman star who used his voice and stories to lift us into higher realms of thought.” But it sounds like you had—in terms of the movie—a large starring role and you were a principal writer and developer of the plot, so to speak.

Yeah, that was my job. Somebody had to do it. It fell on me. No, we all participated in it about the same way! I had a big part in it. Kesey, of course, who was my partner, and Cassady, who was the star of the whole show. And all the other Pranksters, all co-workers, we all grooved together when we did stuff. We would do spontaneous performances all the time, everywhere we stopped. We'd play our instruments and cavort around the bus and make up stories and get a lot of people joining in on it. Yeah, we were kind of like a traveling goofy circus.

And in terms of Further — the psychedelic-painted bus, itself — it wasn't merely your transportation device. It was a co-star in the movie, wasn't it?

Oh yeah, the bus was a main character. Without the bus, you know, we couldn't have done all that stuff we did. The neat thing about the bus was that we installed a sound system on the inside and the outside, with microphones and headphones on both. We were all communicating with each other, and it was going out of the speakers. And Neal Cassady had a microphone hanging down in front of him, and he was talking into that all the time, the sound going out. So when we were going down the streets of New York, we were talking to the people gawking from the sidewalks. It was really terrific to be able to talk to each person and say, “Oh, there's a beautiful woman in a fur coat, and it's only 95 degrees out. Why is she wearing such scanty underwear today?” Things like that.

What was your first psychedelic trip?

Well, it was when Kesey was working up in the VA Hospital in Menlo Park, where they had been doing experiments, and LSD was one of the drugs that he had previously taken as a volunteer. And it was quite an experiment! And then one night, when he was there working as an aide, he saw that the office of the doctor who ran those experiments was right there in the room where he was. So he saw the key on the wall, and he unlocked the door and went into the room and was snooping around. And he went to the desk, and he opened the middle drawer, and he found a box there full of LSD tabs. And so he just pocketed those, and closed the door and locked it up and everything. And then we had LSD to experiment with — on our own terms — usually around Kesey's house.

And what did you get out of or learn during your first psychedelic experience?

The world is wonderful. People are pretty good, even though some people are misguided and do bad things. But, all in all, it's a beautiful place. It's a wonderful place to live. Your family and friends are great to hang out with. The bounds of creativity are unlimited. Play our instruments. Writing. Or whatever we were doing. You can go, go! — blow, blow hard! — just like in jazz. You know, it opens up your mind, LSD, to things you didn't see before, and the wonderfulness of everything. Yeah, for me, it was a terrific thing. But I haven't taken LSD in years and years and years.

And why is that?

Well, is it still around? Where do you get it? [Laughs]

I was going to ask you, Ken. [Laughs]

Oh, you want some! No, I'm not interested in that anymore. I'm happy with the way everything is now. My brain is wide open.

Another one of the substances that Kesey was able to, let's say, “liberate” from the VA Hospital in Menlo Park was IT-290. Can you describe how that was different than LSD or what you experienced, maybe on IT-290?

IT-290 was way more powerful, and you really had to take a little bit of it. But it was clean and clear, and you'd be high for a long time. Yeah, it was clean. It was special, but it was also something you didn't want to do all the time.

There are combat veterans who are using psychedelics today to help with dealing with PTSD. Did any of your early experiences with LSD ever help you process or deal with any experiences you had in Vietnam in the early '60s?

No. They never related to one another.

Were there any psychedelics in Vietnam, while you were there?

Vietnam, huh? There must have been...I think Kesey would send me stuff every once in a while. That's right, I'd be on R & R, you'd be away from the squad room. You'd go to somewhere like Japan or Hong Kong. So, I'd take a little LSD; once in a while, I did that. But I never did it when I was actively flying helicopters.

No, I didn't suspect so. [Laughs.] That would have been a little too much. That would have been like Apocalypse Now! or something.

[Laughs.] Yeah, right! That's a great opening in that movie. Really something.

What do you think about the regulatory framework and what's taken place in Oregon regarding psilocybin? That you can go and have a trip on mushrooms in a room and put on eye shades and listen to music and have a guide there in case something goes awry. What's your thoughts on all that?

Absolutely nothing. I never think about it. Why would I think about shit like that?

Why do you describe it as “shit like that”?

Well, there's lots of shit like that going on all around us all the time, and you don't have to think about it or participate in it.

Gotcha. So, I'm very curious: In the book, I learned how you attended — along with Ken Kesey and with your brother John and with Ken's brother Chuck Kesey and his wife Sue — the 1962 World's Fair in Seattle. And you say in the book that you took psilocybin mushrooms.

Yes, we did. That was fun! That was really fun. You know, the theme of the scene was “Man in the Space Age.” So, they had all this futuristic stuff there, and you could walk down through it. And one of the things that I remember the most was they had typewriters. So, you could type stuff on them. I'd never seen this one typewriter before; it was a revolution, I tell you, because it wasn't a regular typewriter, individual hammers flying up there against the paper. There was a ball that sat there. And when we typed, that ball turned, and bonk, bonk, bonk--you could type as fast as you possibly could! It was the IBM Selectric. I decided that when I left there, I was going to buy one and have that for my writing. And so, I did. And I still have that IBM. It's really a great machine.

You were in Oregon before all of you went up to Seattle, tripping at the top of the Space Needle. Do you think the psilocybin mushrooms were from a local forest or pasture?

Must have been. I don't know where we got them, but we knew people who had that kind of stuff. So, we got some, and we chewed the mushrooms before we went into the fair.

In terms of the Acid Tests, you write, “Who put the acid in the Kool-Aid? [The Merry Pranksters] never knew nor cared. Our bit was to put on the show.” But, a couple of paragraphs later, you mention psychedelic chemist Owsley being there. So, it's fair to say he, more than likely, put the acid in the Kool-Aid?

Yeah. It's easy to say. So, say it!

There were other underground chemists around the same time, weren't there in the Bay Area? Not just Owsley?

Oh, sure, yeah. He didn't do that all by himself, no. But he was the guy we knew who hung with us at the Acid Test. We didn't know any others.

Owsley had two trash cans full of Kool-Aid. And one said, “ADULTS ONLY.” And the other one said, “FOR KIDS.” And the adults-only one was loaded with LSD. Everybody could drink that, and get high. So, that was a lot of fun. That was called the Muir Beach Acid Test. That was the first one. Well, it wasn't the first one, but it was the first public one like that.

In terms of musical groups, there's a band that you're known for having hung around with called the Grateful Dead. At one of the early Acid Tests, Owsley listened to them and said, “These guys could be bigger than the Beatles.” Did you ever get that kind of sense about them back then?

No, because it wasn't like it was some kind of commercial thing that would be big like that with making records and all that. They were a group that played at the Acid Test. They liked to play together with us, Pranksters, and were terrific on their own.

When we quit doing the Acid Tests, they kept on playing. They had no idea how big and famous they would become. But no surprise, really, because they were so good. And they were doing songs in which they would take off from the lyrics in the song and go to places and explore other things in the middle of the song and then come back to the lyrics again. Yeah, there was nothing like them. The Grateful Dead, they were phenomenal.

And you worked for them for a little while?

Well, I didn't really work for them. I worked with them, did stuff with them and hung out with them. The guy I know real well, and he's still a good friend, is Bob Weir.

And Jerry Garcia?

Oh, yeah, he was one of my best friends. He lived up the street from me in California, just in an area south of San Francisco. And I'd go up to his house all the time, and we'd hang out and shoot the shit and talk and everything. We became really good friends.

In Veneta, Oregon, in August 1972, you were onstage with the Grateful Dead.

The Springfield Creamery put it on. They put it on to raise money. They needed money to keep their business going. They got the Grateful Dead to come up and do that concert out in the Oregon County Fair field. And I was the emcee for that. The other thing I was the emcee for was in Woodstock.

That must have been the most people that you've ever spoken in front of in your life.

Yeah, really, for sure: 400,000. That was a lot of fun.

You had kind of an itchy-scratchy relationship with Owsley. He didn't always look at you favorably all the time. Is that right?

Oh, he thought I was a real idiot! Oh yeah, he was a brainiac, you know. I was a wild guy, right, and I made fun of him all the time, too. Fucked around with him. So, he didn't like me too much at first. But, naturally, we ended up getting along real good, being friends.

You point out a couple of different experiences with folks in the book who are on acid and your reaction to them. At one Acid Test, there was the “Who Cares Girl,” who you went up to and put a microphone in front of her as she was saying, “Who cares?!?!” Is that correct?

Yeah, right. That was good. Somebody tripping out, yakking, so we miked her up, so everybody could listen to it.

But wasn't it projecting a freak-out to the whole crowd?

Well, what the fuck, everybody was freaking out! So, it was just part of the fun, I mean it wasn't harmful. It wasn't malicious in any way. You know, it was all positive.

There's another part in the book where you're assisting with a music festival in Texas. And there's a fellow named “Tennessee,” and he's in the throes of what appears to be a bad trip, and people are holding him down. And you go up, and you say, let go of him, and you take him, and you hold him in your arms, and you say to him, “You be what was meant to be, and what is meant to be is that you be here with me.”

Oh, that's good! That's a good poem.

Is that advice you would give to people who are in the midst of someone who's having a bad experience? What have you learned about that?

Well, that was the only time I did that. And, that guy after he'd settled down became a part of our group. He became kind of like our bodyguard. He'd always hang around in front, and if anybody started fussing, he'd go calm them down.

What would you tell a young person — or, perhaps, something you've said to your own children — regarding psychedelics?

Be careful. [Laughs.] I don't know, I've never had to do that really. It's something to experiment with, but you gotta be careful. It can harm you, but if you do it right, I guess it's okay. It's okay for me.

There's a quote from Ken Kesey that's in your book. He says, “When people ask what my best work is, it's the bus. Those books [One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest and Sometimes a Great Notion] made it possible for the bus to become.” What do you feel your best work is?

My best work? Oh, right here at home: I bought the property, I built the house for my wife and kids. This is my best work right here. I mean, you know, books — I've written a few books. That's okay. But no, living right here in Oregon, in this place, and being part of the scene here. It's really good here in Eugene now, because it's a small enough town where you can perform and know all the performers and be part of the musical and theatrical groups here. This is the best.

How was today's feature story?

💌 If you loved this email, forward it to a psychonaut in your life.

Editorial Process

DoubleBlind is a trusted resource for news, evidence-based education, and reporting on psychedelics. We work with leading medical professionals, scientific researchers, journalists, mycologists, indigenous stewards, and cultural pioneers. Read about our editorial policy and fact-checking process here.