- The Drop In by DoubleBlind

- Posts

- Searching for Freedom on the Road with the Dead

Searching for Freedom on the Road with the Dead

Ahead of the Dead’s 60th, one writer reflects on what it *actually* means to chase freedom on the road.

Deep dives and investigations

you won't find anywhere else

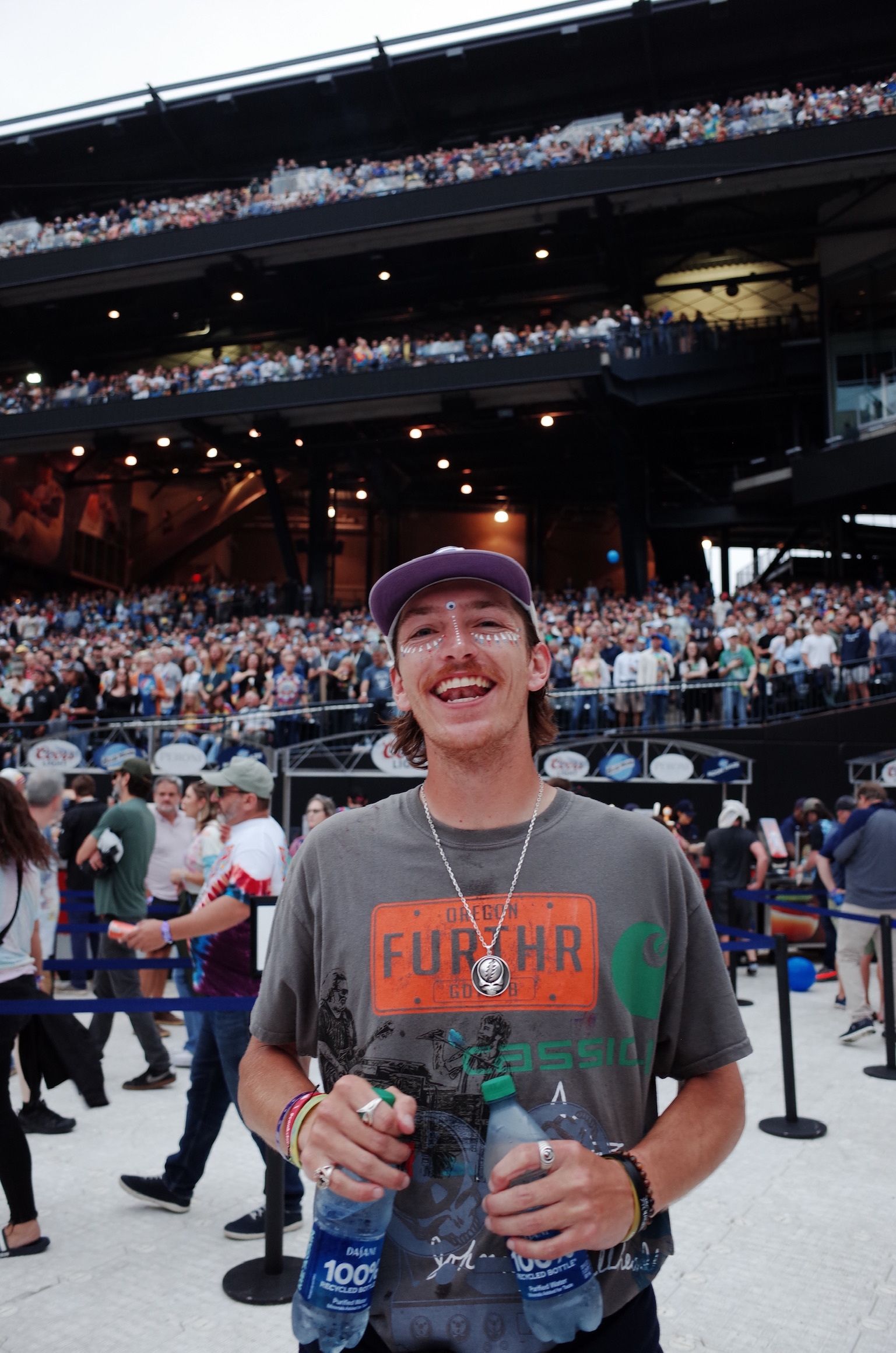

On the Road with What's Left of Deadheads

Ahead of the Dead’s 60th anniversary shows in Golden Gate Park, a summer on the road with what’s left of their fanbase community looks at what it means to lose yourself in the search for freedom.

By Rose McManus

Photos by Michael LaRosa

My landlord comes over to fix the smoke detector that won’t stop beeping. A refusal to die that I have to admire. A Dead show plays through my speaker, and he says, “You’re too young to be listening to this.”

Great, now he thinks we’re some kind of wake-and-bake household. We are good, pious tenants, I’d like to convey.

“I was living in San Francisco when Jerry Garcia died, in 1990,” he says. (Jerry died in 1995.) “He was so young, like in his 20s.” (He was 53.)

“You saw Jerry in utero!” my parents have often told me. Also not true. (“Actually, it was Los Lobos. And you were already a baby.”)

Becoming a Deadhead came later, a kind of mid-20s oopsie. To be Dead-curious is to be Dead-vulnerable. No one warned me that in the summer of 2023, I’d end up at my 29th show in two months — desk job and girlfriend left behind in New York.

The Grateful Dead first played 60 years ago, and Dead and Company 50 years after that. At my first show, I didn’t know John Mayer was in the band. Our new Jerry, sailing on a half-rebuilt Ship of Theseus alongside some original members. Amen! I am not pedantic about eras or sound setups. (But much love to those nerds.) There are heads who can glean a year from its notes like a fine wine. I am more like the guy who tastes a Costco sample and says, “Yummy! I will take 400, please.”

Moderation is for those who skip the highs because they can’t handle lows. I left home that summer at the mercy of curiosity and a little too tantalized by the idea of becoming unknown. In response to the burden of schedules and commitments, it was endearing to have two months with only one place to be: wherever the band was. But to try to understand the winds that blow the Deadhead dust through the decades is to accept that you might get swept up before you find the truth.

***

The tour started in LA in May 2023. It was easy to slip in as a young woman with a girlfriend back home; I was one of the girls but also one of the guys, with their girlfriends back in Gilroy or New Orleans. Mine was back in NYC. E-Z UP tent diversity hire, I suppose. I was regularly handed spit-soaked joints by strangers before we hit the open road, leaving California behind. Apparently, if you show up at the same place at the same time every day, you wind up seeing the same people. And some of them even become your friends.

“I was like OK, she’s like, kind of square,” my tour friend Zach said of his first impression of me. Zach dons long red hair under a hat, sometimes in pigtail braids. He’s in his late 30s and started touring in 2017, at first drawn in by the drugs. I would be offended if he weren’t kind of right, but we’re friends now anyway. In Phoenix, Arizona, he made an introduction by offering shade; a month later, I was riding in his van.

Following the Dead is akin to a two-month urban camping trip. Food in coolers, beds in parking lots. Each day is brand new, Dallas to Atlanta or Pittsburgh to Philly, but showtime is always around 7:00pm. Before that, you might be hawking T-shirts or crystals or beer to locals in the parking lot. Shower at a truck stop, rinse, repeat. Breakdowns, gas siphoning, and a new friend hitching a ride. 19 cities, 29 shows. Coast to coast and back. And if you have a free moment, you call your mom and tell her you’re safe.

There is a purpose to all this, and that’s to get into the show. At its best, a Dead show is a vehicle for transcendence — a liminal moment conjured between the audience and the band, with soundwaves acting as the glue that binds them. The feeling is so enamoring, my new tour friend Jeff says that being on tour “feels like being in love.” The way communion between two spirits conjures an unmovable, warm glow, allowing one to see places in the universe or the mind that are not otherwise visible. Sometimes I think about it like two mirrors facing each other, creating something infinite.

Dennis McNally, the band’s former publicist and biographer, says that Deadheads are part of the band. At least the original fans were. “The audience was their partner,” said McNally. “Everybody in the room is a member of the Grateful Dead.” In a quest for what, originally? “To change the world.”

Sure, I’ll take it.

McNally makes me feel like I’m living out some kind of divine defection in the form of grilled cheese sandwiches. “Hippies create police, police create hippies,” the Ram Dass platitude goes. But who really inspired the hippies were the beatniks of the ‘40s and ‘50s. The creative vagrants called on Americans to live a fuller life, McNally says, rejecting materialism, traditional values, and hometowns. He believes there’s an impulse in everyone to explore. But beyond that, some of us are particularly prone to wander toward the light.

I flew from Phoenix to Dallas three shows into the tour, just like I’d planned. But the rest of the tourheads were driving through the desert, without air conditioning, for 16 hours. I shouldn’t have booked a flight, I realized, and didn’t want anyone to know I hadn’t driven. My Excel spreadsheet commitment to tour — with days, destinations, and companions labeled in cells — had, ironically, marked me as an outsider.

***

At the 9th show, outside of Pittsburgh in early June, the dusty lot had an edge to it. Cop paranoia around bootleg tees and an arrest. Bootlegs are tolerated by the band as long as they obey certain boundaries. A shirt can’t say “Dead and Company,” but it can say “Phil Me Up, Daddy” with a picture of bassist Phil Lesh and the iconic skull “Stealie” motif.

The band’s iconic motifs foster creativity. Psychedelic journalist Jesse Jarnow says the original Dead were a catalyst for misfits to come together and endeavor in something artistic. “Anti-authoritarianism, anti-cop, misfit power, freak power.” He describes it as a place “where the weirdos are in charge.”

When we eventually arrive in New York City for the 17th and 18th shows, the parking lot scene is a scene of urban chaos. I counted hundreds of tents from the pedestrian bridge overlooking Citi Field. Music, balloons popping, crowds, and carnies rolling with the band and attending the show rivaled that of Times Square. Recently, my tour friend Emahn told me about “TAZ.” Temporary Autonomous Zones, a ‘90s-era anarchist shorthand for pop-up pockets of self-rule. The lot scene is one, he tells me. Not a place without rules, but a place with its own that differ from the rest of society’s. It’s hard to understand why venues let us do this.

At Citi Field, cops rested just on the boundary of the parking lot, making it feel like everything inside belonged to us. The tourheads used to “circle the wagons” on the lot, protecting their own first and foremost and defending the lawless order within, Dr. Rebecca Adams tells me. “Outsiders were discouraged,” she said. People needed to trust that you were really there for the music, that you weren’t just trying to make a dollar or get high. All of that was fine, of course, if you could at least name a heady show or two.

Adams is a professor at the University of North Carolina Greensboro who has studied the Dead since the 1980s. Now in her 70s, she’s recovering from a hip replacement when we talk — her “Hippie hip,” she calls it. Her surgeon thought she had been a truck driver based on the wear on her right side. “You’ve driven a lot of miles on that hip,” he told her. Tour is visceral, same as it was in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

I met an old head named Tessie in Saratoga Springs, New York, her tent was set up next to my friend Zach’s. She recalls it similarly: There were arrests, peyote all over the ground. And lots of nitrous oxide, which still persists. Twice on tour that summer, friends of mine took a hit from a nitrous balloon and collapsed on the ground, hitting their heads. I don’t touch the stuff. The bright popping latex is too literal for me. Sad clowns after the circus, when the show is over.

Tessie’s in her 50s now, still spinning to the music with long hair and flowing skirts. I asked what happened to the rest of her generation of tour kids. “Did they get wives and kids?” I asked her.

“Or [they] went to jail,” she responded. “Or died.”

***

The Dead has been playing some of these venues for decades. In Saratoga Springs, Zach nodded as a gesture toward a Head, then toward the nearby woods, and said: “She’s from the mist.”

This was Zach-speak for someone who was fully in it, a mystical being connected to the energy of the Dead. Someone who definitely doesn’t have a work laptop, has definitely never been to Erewhon in LA like me. (Had to try it.) “Mist people” are those conjured by the spirit of the music itself.

“There’s critters on the lot that we suspect don’t exist in normal reality,” he told me again recently. You never see them at a gas station or outside the perimeter. Who is and is not “from the mist” became a taxonomy, and this went on for a bit that day in Saratoga. Anthony is from the mist. Jeff gets it, but he isn’t from the mist. Faith is from the mist. I am most certainly not from the mist.

Deadheads slither through cultural cracks, a Where’s Waldo of motifs always in view but only in clear focus when they’re passing through your town or urinating on your lawn, Deadhead scholar Adams said. “Weir everywhere,” Deadheads say, a corny pun reference to guitarist Bob Weir. Adams is wearing a tie-dye tee when we talk. I ask who made it. “Corndog,” she says, with no trace of irony. In the parking lot, “Rose” sounds like a name I picked myself.

Even as I chased the music along I-70 across Indiana, Illinois, and Missouri, I still considered myself a skeptic. I thought about the search for answers that never come. Absurdist philosophy views the search for greater meaning as an end in itself. In a prison of meaninglessness, Deadheads show the world that the rules for what you look like, where you live, and how you spend your days are self-imposed.

Sometimes I started to believe in the magic of it all. Once you’ve given up your home, clothes, job, even your name, perhaps the universe and time itself start to unbuckle. Every defection from society is a moment of protest. Whether or not the normies understood was perhaps the point: Their misunderstanding was a sign of success. And on top of it, me and my new friends were having fun.

***

Around the halfway point of the tour, in late June, I created my own bootleg merch to sell alongside those of the other lot artists. “Jery Garcia” (purposefully misspelled) on 12 camo trucker hats, my idea of a joke, I guess, distancing from the deep earnestness of the real hippies. My artistic expression revealing my own chasm of identities, if you looked closely enough.

I wasn’t the only one caught in a Deadhead identity straddle. At the end of June in Boston, I met Josh Hitchens, the band’s tour photographer. The real roadies call him “Wook” on account of his long hair and past life as a fan on the road. (He still sleeps in his car when he tours, even if he’s working.) Photographing the band ruined the music for him, he says. His own love of the show brought him backstage to see how the sausage is made, the real grit behind what he used to believe was a magical, mystical thing.

Among the real Heads, it was better to be fully in it. In society, it was better to be fully out. Dr. Adams sent me a study she co-authored on “mixed marriages,” meaning relationships where only one member was a Deadhead. A common cause of marital strain.

The Cheshire Cat to Alice, “We’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.” Josh’s madness had taken him into professionalism. Mine led me to a breakup.

Most of my tour friends never met my girlfriend. She was supposed to join for one show — Indiana, known for its iconic lot at Deer Creek — but a major storm on the east coast canceled flights. My own journey was detoured before I finally reached my destination. I was hurt and couldn’t believe she didn’t want to meet my brand new friends from druggie summer camp. When things with her were rough, Zach said, “Remember, she’s normal. You’re the one who’s tripping.”

Deadheads “bought into the idea, which grew flimsier each year, that following a rock band from football stadium to football stadium, fairground to fairground, constituted adventure of the Kerouac kind,” Nick Paumgarten wrote in the New Yorker almost 13 years ago. Phony vagabonds, he calls them.

Kerouac was an inspiration for Jerry. On the Road was the template for his life, McNally says. The book called upon Americans to live a fuller life, to not just be “economic robots.” In their rejection of the structures of traditional American identity and materialism, the hippies and beatniks imagined a freer world, McNally says.

But I wondered if a Kerouac pilgrimage to freedom is phony, too. In his book Satori in Paris, the meandering beatnik claims to experience a flash of enlightenment or “satori.” But the exact moment eludes even him. He stumbles through cafés and train stations, runs out of money, and flies home in a panicked rush. I looked at my old tour logs. I was losing weight, my body conforming to time spent on my feet and a scattershot meal schedule. Family fights, missed calls, parking lot beers, and me claiming I’m the happiest I’ve ever been. Freedom by way of freefall.

I hitched a ride in the back of Zach’s cargo van after Boulder closed out the 24th show, canceling my flight to Spokane to sit unbuckled on a cooler. July 4 was spent passing through Wyoming and Montana. I felt so far from home. Two nights at The Gorge, a journey through Oregon, and two months after leaving home, the end of the tour met us back in California. San Francisco, specifically: The birthplace of American counterculture and the Summer of Love.

***

Beatnik writer Ken Kesey’s son Zane was selling tie-dye toilet seats at the waterfront vendor scene just south of Oracle Park; the preposterous thrones are a reminder of watered-down legacy passed on. Beyond the toilet seats, past the enlightenment pamphlets, and around the man with the chest tattoo proclaiming, “Reject Humanity Return to Monkey,” Dead and Company played their final show that summer, on July 16. A symphony of hissing nitrous tanks and balloons popping served as the night’s encore.

Later that month, I went back to work. My girlfriend and I broke up the following winter after a few months of unraveling. Zach said it was because I got a “dose of freedom world.” He tells me about another tourhead who got dumped when she returned home. “Because she came home with a new dog, a new van, and the intention to be homeless.” She ended up inheriting a house, he said. Sometimes, I agree with Paumgarten: Deadheads are phony vagabonds, pretending to rough it.

And they’re definitely not a counterculture, Dr. Adams says. Not with two Sphere runs. Last year, the experience machine of the Dead reached its (un)natural destination in the desert, at the orb-shaped venue called the Sphere. “The ultimate surveillance borg,” Jarnow calls it, the opposite of the DIY culture of the Dead. The original heads used to joke that the band would retire in Vegas, Tessie tells me.

***

My friend Jeff from that summer texts me this past May asking about my girlfriend. “Congrats!” he says when I tell him we split. My phone spits out confetti. In my apartment, the smoke detector is quiet, no longer playing its relentless low-battery beat. He asks if I’m heading back to San Francisco for the 60th anniversary shows in August. I am. “Freedom world” still beckons, apparently.

Dr. Adams won’t be in San Francisco for the 60th. Not accessible enough for her new hip, she says. For the older heads, she wonders how they’ll fare at a venue like Golden Gate Park. It’s hard to imagine her and her cane standing in a field for hours. McNally won’t be there either, despite being local. Too big of a show for him, at his age. The legacy, Adams says, can’t be enjoyed by the demographic who built it in the first place.

What is the right way to leave a legacy? Perhaps via a gradual transition to a complete replica? It’s hard to know if Bob Weir is shrinking himself in preparation for his astral exit or if he’s taking up space in resistance to a psychedelic ego death.

Flipped backwards and shrinking in the rearview, like Alice after consuming the “Eat Me” and “Drink Me” treats, my own satori is recast. Burning gasoline and missing calls, saying “I love you,” to strangers until it became real. I was chasing something others couldn’t exactly see, which still makes me wonder if it was true.

“All versions are true,” Phil Lesh told the New Yorker in 2012 of beat-up tapes and bootleg song recordings. “The more versions there are, the truer it is.”

I sold all my “Jery Garcia” hats except one I kept for myself. Maybe down the line, I’ll insist that’s how his name is spelled. Every person's experience is a part of this reality, McNally says. The good shows, the bad ones, the mediocre ones, and even the hallucinations build to create something real. Does all of this make for a freer world? Maybe, or perhaps it’s just a new generation of wayward weirdos, still building the story of the Dead, 60 years later.

How was today's feature story? |

💌 If you loved this email, forward it to a psychonaut in your life.

Editorial Process

DoubleBlind is a trusted resource for news, evidence-based education, and reporting on psychedelics. We work with leading medical professionals, scientific researchers, journalists, mycologists, indigenous stewards, and cultural pioneers. Read about our editorial policy and fact-checking process here.

Reply